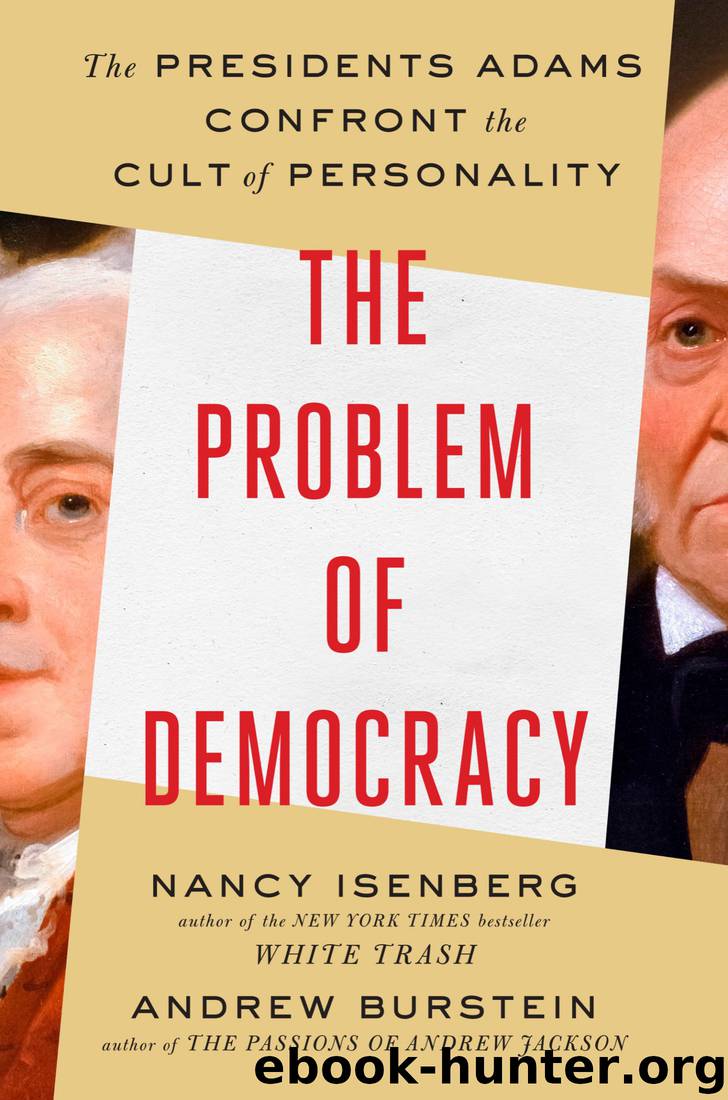

The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality by Nancy Isenberg & Andrew Burstein

Author:Nancy Isenberg & Andrew Burstein

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Non-Fiction, History, Politics, United States, Biography

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2019-04-16T00:00:00+00:00

HEAPED UPON

John Quincy Adams attended Madison’s inauguration on March 4, 1809, and was present as well at a ball that evening attended by the outgoing president, Jefferson. “The crowd was excessive,” Adams wrote in his diary, “the entertainment bad.” He had returned alone to Washington and was earning his living at the bar. He argued before the Supreme Court on behalf of the defendant in a case that concerned the disposition of Georgia lands. On March 6, as his case wrapped up, Madison called Adams in for a meeting and said he would nominate him for the Russia post. How long would he be expected to remain abroad? the ex-senator inquired. For an “indefinite” period, returned the president, perhaps three or four years. It would turn out to be twice that—the entirety of Madison’s two terms.3

A few days after their meeting, John Quincy booked stagecoach passage north and ruled the roads out of Washington worse than he’d ever seen them. Arriving home after ten days, he found his family generally well and knowledge of the president’s offer to him already widely disseminated. A writer in the Boston Gazette immediately pounced, accusing both Adamses, father and son, of enriching themselves through government appointments, each having returned from Europe “with a pretty fortune.”

It wasn’t true, of course, but the Gazette was not interested in fair play. The son, in particular, since his return from Berlin, had not been “six months without holding some office of high honor, profit, or trust,” the story went, and now, “both parties seem to vie with each other in favoring him.” The writer, signing his name “SPARTACUS,” made noises about the Adamses entertaining ideas of a hereditary presidency. John Quincy wrote directly to the editors of the Gazette, asking “SPARTACUS” to reveal himself in order that he might know to whom he should pen a thoroughgoing response for publication in the pages of the newspaper. He received an evasive, sarcastic reply mumbling something about journalistic ethics.

Meanwhile, the Anti-monarchist and Republican Watchman delighted that the Adams family were “converts” from Federalism. “Is not this proof of itself sufficient that our cause is just,” the article smugly surmised. What greater loss to the ranks of the Federalist Party could there be than the desertion of the Adamses? A more skeptical Massachusetts Spy contrived a scenario in which John Adams could have become so distraught over the Republicans’ ascendancy at his expense that he conspired with his son in 1805, just after Jefferson’s reelection, to keep their family in power through any means necessary. If the embargo presented itself as a “plausible and speedy pretence” for the perturbed pair to advance themselves, the son’s failure to retain his Senate seat gave them their just deserts. “Ah Messrs. Adams,” this critic oozed, “you ought to have known that honesty is the best policy.” Instead of the son sitting imposingly in his Senate chair and the father enjoying “otium cum dignitate” (ease with dignity) in his retirement years, the younger was left

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| U.K. Prime Ministers | U.S. Presidents |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37815)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23090)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19053)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18596)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13341)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Educated by Tara Westover(8060)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7493)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5852)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5642)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5284)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5157)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5103)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4820)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4367)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4117)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3973)